The young curator Saverio Verini offers, in his new book, La stagione fatata (Castelvecchi, 2022), a new perspective on childhood, redeeming it from the alleged “aura of untouchability”, to open it to unusual readings. The book was presented in the Sala Scarpa of MAXXI in Rome, on 21 February. The evening was introduced by Bartolomeo Pietromarchi (director of MAXXI Arte) and, in the presence of the author, there were speeches by Cecilia Canziani (curator), Manuela Pacella (art critic and teacher), Cesare Pietroiusti (artist). The debate was moderated by Alessandra Mammì (art critic and journalist). On the occasion of this evening I had the opportunity to interview Saverio Verini.

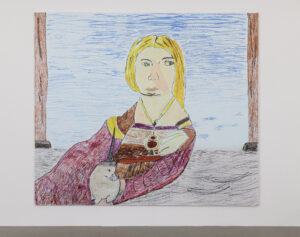

Vedovamazzei, “Early Works (Raffaello all’età di 7 anni)”, 2021. Oil crayons on a canvas, 290 x 335 cm. Installation view at galleria Magazzino, Rome. Ph Giorgio Benni

Starting from its genesis to its conclusion, has the book generated in you further reflections and questions in relation to the theme of childhood?

I was invited by Christian Caliandro, art historian and curator of Fuoriuscita, a series published by Castelvecchi, to write this essay and I chose to address the theme of childhood, because I believe it has an inexhaustible potential. As you may have noticed from the reading, the book creates a constellation of Italian artists very far from each other. There we find painters, such as Luca Bertolo or other artists, such as Vedovamazzei, ranging between more media. I like to bring together different artistic personalities through a single key, which is that of their multiple interests or emotions. A theme such as childhood has in itself the ability to adapt and keep together not only the visual arts, but also literature and cinema. However, it is always the contact with artists that arouses in me the initial curiosity.

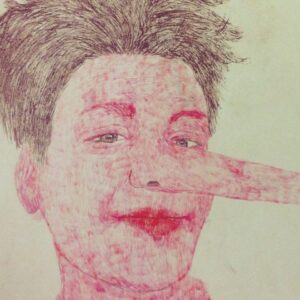

Marta Roberti, “Autoritratto come Pinocchio”, 2016. Oil pastel on paper, 29.7 x 42 cm. Courtesy the artist

In fact, the most interesting thing was the willingness, on your part, to argue and deal with the broad-spectrum issue and not only sectorially…

I believe that there is a need on the part of authors, artists and other intellectuals to try to connect to a part of themselves and their own experience, that somehow they feel is a source, in its dual benevolent and malignant nature, and that it is the origin of many influences, interests and even traumas, basically, that inspire the work. And then, realizing it personally, in retrospect, I think that there is the will to treat childhood only as a golden age, almost deified and associated only with carefree play. In part, of course, it is so, and it cannot be denied, but it also contains a more delicate aspect, such as the presence, for example, of traumas, impositions and experiences that reverberate throughout our experience.

Luca Bertolo, “Il fiore di Anna #2”, 2019. Oil and acrylic on canvas, 200 x 250 cm. Courtesy SpazioA, ph. Camilla Maria Santini

Childhood is a return to the origin and therefore a departure from the rational capacity of man. Considering the etymological translation of “rational” – from the Latin reor, “to estimate all that is real” – the infant, on the other hand, uses imagination bringing into the present nothing through the game as, for example, in “let’s pretend…”. This aspect can strengthen, in adults, the possibility of approaching childhood with a nostalgic attitude, considering it only as a golden age. Do you think that the definition and division between childhood and adulthood can be a convention rather than a real fact?

There’s a paradox, actually. A childhood paradox that’s almost colonized by adults. It is rare for a child to reflect on the nature of childhood; it is always adults who deal with the subject. The situations and emotions of a child’s life are reworked and described a posteriori. In the book, however, I wanted to conclude with Ingresso riservato ad un pubblico di età compresa tra 1 e 6 anni, exhibition by Alessandro Cicoria, curated by Giuseppe Armogida in the COSMO space in Rome, where the use was limited to children and closed to adults. This is a very rare example of how we can actually return a protagonism to the child, giving him voice, without this experience being somehow filtered by the presence of the adult, although it was conceived by the latter. I think it is difficult to get out of this paradox, this contradiction.

Valerio Nicolai, “Capitan Fragolone“, 2019. Foam rubber, paper, glue, oil, enamel, wood, canvas, cardboard, chair, a performer, costume, mask, 300 x 550 x 350 cm. installation view at Quadriennale d’Arte Contemporanea 2020, Roma. Courtesy: the artist, Clima, Milano and Quadriennale d’Arte 2020, Roma

Among the pages of your book it can be glimpsed – in some passages you write it expressly – that the division between childhood and mature age is almost invisible, and that sometimes this clear distinction is created by the adult himself, as envy of childhood. The child, as you write, becomes an adult when subjected to an imposition, or when he becomes aware of the fear of death. It is interesting when, in the first two chapters, you tend to emphasize the value of the unconsciousness of the infant. When the child is forced to know her and to see her indirectly, one asks rhetorically why one becomes adult…

It is a very complex and complex issue, precisely because of the presence of so many thresholds that are crossed and that are part of various individual experiences, from the most carefree to the most traumatic. I believe that childhood has its peculiarities, of course, but it is also true, as we said, that the separation between childhood and adulthood is less marked than what you want to believe. The child, in fact, even with a dimension, a physical format and different cognitive abilities, poses, after all, the same problems and has the same exaltations that an adult poses, and that’s why play and fears are the elements that you tend to pursue for life.

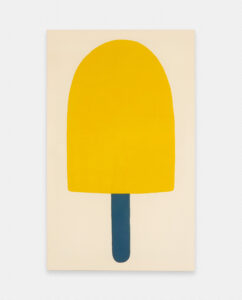

Adelaide Cioni, “Go easy on me, one yellow with blue stick“, 2020. Stitched fabric on canvas, 130 x 80 cm. Courtesy: l’artista e P420, Bologna

Based on this topic, I would like to talk about the video Ball Don’t Lie by Roberto Fassone that you included in the book. Here, the artist is busy shooting the ball, and the result of the gesture determines the answer to existential questions that appear to the observer.

In the work there seems to be a short circuit between the carefree play of childhood and the task of questions and questions of a rational and existentialist nature. The video, in fact, plays on this suspended dimension as a very quiet rhythm: a sharp contrast between a person playing basketball, training alone in a carefree way, and the presence of these questions that follow the rhythm of the ball. The work Un giorno tutto questo sarà tuo by Mattia Pajè is treated in parallel with that of Fassone: here the photograph of a newborn, who sleeps tenderly, is contaminated by three black spots, which allude to that uncertainty and responsibility that the adult gives to the infant, with the passing of witness.

Filippo Berta, “Happens Everyday”, 2012. Performance, Diasec print, 120 x 67,5 cm. Courtesy: l’artista and Prometeogallery di Ida Pisani

The figure of the artist tries to remain alien to traditional, conventional and systemic logic of the work, as well as to the mantra of producing to earn. With this attitude, he claims the freedom of expression of the artistic act, the same freedom that the child expresses in playing. There is a clear reference to the third part of your book, in which you emphasize the return of a frugality in art, in contrast to technical-scientific advances. Do you think, therefore, that there is a return, or a need, by some artists, to want to return to the original value of things, considering childhood in its ambivalence, as a period of carelessness but also trauma?

There could be, on the part of artists, this tendency to associate the idea of progress, in all its forms, to the idea of utility and functionality, elements that art often distances. I believe that adults look to childhood as an age of “purity” and transparency, where needs, desires, fears and traumas emerge in a more intense and imaginative, instinctive and uncontrolled form, the one that artists tend to pursue.

Alessandra Andrini, “Biglia”, A14 Km 50, 2005. Polymethacrylate, fiberglass, steel, printing on PVC, neon tubes, diameter 4 m. Courtesy: the artist

I would conclude with the quote by Eugenio Scalfari inserted in the beginning of the book. Childhood, for Scalfari, is “the only one of a lifetime that never ends and accompanies you until your last breath”. Do you therefore believe that adulthood is a loosening from our original self?

That would be a very nice image, this, to consider. And I think that artists, more than others, have the privilege of preserving the memory of that feeling of wonder that springs from the constant discovery or of always looking at the world with amazed eyes, like a child.

Giulia Pontoriero

Info:

Saverio Verini, La stagione fatata, 2022

128 pp., 16 euro

Castelvecchi editore

Graduated in Architectural Sciences at the Sapienza University in Rome, with a master’s degree in Contemporary Art and Management at the Luiss Business School, she currently works as an intern and project manager at Untitled Association. Graduated in Photography and Art Criticism in Bologna, she currently carries on her personal projects and is part of the team of the Forme Uniche cultural project.

NO COMMENT