On 7 September 2021 at Villa Mirabello in Milan, on the occasion of the opening of the international exhibition “(is) nature dead?” curated by Sabino Maria Frassà, Stefano Cescon was proclaimed winner of the eighth edition of the Cramum Prize for art in Italy, whose goal is to identify artistic excellence and support younger artists in a socio-economic context of particular fragility for emerging generations like the current one. The commission, made up of 12 internationally renowned artists present in the exhibition out of competition and a scientific committee made up of well-known gallery owners, journalists, collectors and intellectuals, expressed itself with the highest degree of agreement in Cramum history. The victory is for the artist the starting point of a series of exhibitions and publications that will end in two years with a solo show at the Francesco Messina Museum in Milan. Stefano Cescon (Pordenone, 1989), graduated with honors in Decoration at the Venice Academy, focuses his artistic research on the exploration of the expressive potential of beeswax. The work that earned him the title of winner belongs to the “Honey Boxes” series, which investigates the balance between antithetical aspects, such as natural and artificial, human and meta-human. To deepen this research, we had the pleasure of asking him a few questions.

Emanuela Zanon: The main materials of your work are paraffin, beeswax and pigments: how did you come to the development of this technique (which at the moment is your expressive feature) and through which processing phases do you arrive at the final work?

Stefano Cescon: This journey began about three years ago thanks to an uncertainty regarding the common pictorial practice. I realized that many formal solutions I adopted, although functional to the final result, had already been iterated and investigated. I felt the need to overcome the two-dimensional character of the pictorial surface and the only possible way was to try to approach a three-dimensional, relief dimension. This sensation was soon followed by the discovery of plasticine (a typical sculptural modeling material) used in a laboratory course at the Academy. This awareness of the material’s potential, its ductility and elasticity, was fundamental in seeking a dialogue between the visual experience of (oil) painting and the tactile one of sculpture, using the organic character of both as a bridge. From that moment on, a phase of discovery made up of trial and error followed, up to the elaboration of the “sedimentation” as a gestural action that best expressed the character and strength of the research. From a technical point of view, most of the time is spent in the creation of wax blocks (paraffin and beeswax in different percentages) colored thanks to the pigments contained in the oil colors: I always look for a wide assortment of these tones because they constitute the “Painter’s palette”, followed by the decision of a chromatic scan as coherent and fluid as possible.

What is the relationship between randomness and design in your creative process, also taking into account the color and material adjustments that the natural elements will have over time?

As mentioned before, I always look for a dialogue between complementary aspects, both for expressive reasons and to give the work greater resistance and durability over time. There are different dynamics that occur in the creation of a single piece, as far as I am concerned the external agents and the seasonality in which the work is carried out are decisive aspects. In this sense, the key word is the balance between the design or the initial idea and the factors just mentioned. These must not be seen as a limit, but rather embraced because thanks to them the final result is never taken for granted. The same relationship between paraffin and beeswax is motivated both by the wide range of expression that this dialogue allows, and by the right degree of solidity and elasticity that they give to the work. The case must not be contained in too tight meshes (as co-author, in part, of the result) and, at the same time, it must be domesticated for expressive and functional purposes.

In your statement you declare that your creations start from the need to propose a dialogue between the daily practice of painting and the virtual aesthetic experience that each of us experiences every day in the social media. Would you like to deepen this bond with us?

Every form of communication brings with it a particular “aesthetic”: this is inevitably also true with regard to social media for a decade now. It seems clear to me that the speed that such communication exerts in daily life also has a reflection in the way we interpret the world, a physical screen that is a metaphor for an immaterial and pervasive one: it is not up to me to judge this fact. At a certain point I wondered how painting could deal with this reality, it seemed to me that any attempt to imitate this “virtual” aesthetic through painting would translate into a form of meta-narration, which in itself does not represent a true problem or a deminutio, but which can become so insofar as it leaves no room for the birth of other languages or is the cause of an aesthetic homologation. Instead, I wanted to pursue a language (as far as possible) less tied to already digested aesthetic references. This reflection led me to ask whether, in fact, generating a process could also generate a more defined aesthetic. Over time I realized that my path led me to look for a primeval form, something ancient, but curiously I approached this awareness by reflecting on this parallelism.

The aspect that I found most fascinating of your works on display is the convergence of superficial imperfections, transparencies and shades in an impeccable aesthetic, which brings to mind illustrious precedents in the field of painting, I am thinking for example of the emotional radiations of Mark Rothko. Would you like to tell us something about the visual references that feed your inspiration (if there are any)?

I have always been fascinated by a certain degree of refinement or pictorial quality regardless of the styles or periods. By this I also intend to include a certain artisan experience that starts from the construction of a frame to the choice of materials. I believe that attention to these elements is crucial for the success of the work. If I think of a work by Rothko, my mind dwells on the relationship that light has with the reflection on the surface of the jute, the texture of the canvas; to this is added a careful play of glazes that delimit defined backgrounds. The strength of his work lies in the balance of these dynamics. If anything, my work is specular: in my case the glazes do not act by overlapping but by sediments of material layers, some reverberations of tones come back to the surface at different layers of distance, the color is not mediated by the surface of the canvas but by the softness of the material, by the wax itself. I have never looked at particular references since I started this path, I don’t want to set myself limits or comparisons; unlike painting on canvas (which has a fair amount of historical background) I feel I am walking a parallel path. Thinking of references in a wider context, I have always admired the research of artists such as Michaël Borremans, Gerhard Richter or Victor Man, authors who have combined the figurative phase of their pictorial research with a formal and tonal cleanliness.

I would end this conversation by asking you what are the main difficulties that a young artist encounters in entering the so-called “art system” and which, in your opinion, are the most useful tools for embarking on this adventurous journey.

With this research I have recently begun to dialogue with the “art system”, I don’t think I have the right tools yet to get to know all the players involved; certainly it is a reality that gives little space to those who face a very crowded scene, but limited by limited perimeters. I believe that those who undertake this path should not ask themselves (at least immediately) the problem of entering the “system”, or rather: the only way they have to do so in a wide-ranging perspective is to concentrate on having a expressive identity, which should first and foremost coincide with a personal need. This brings me back to what we were previously talking about: the risk of the possibility of always staying tuned to an antenna, such as social media, ensures that meta-cognition about oneself and therefore about one’s work is not cultivated. It therefore becomes easier to absorb styles or aesthetics that we have not consciously “sifted through”. My experience leads me to think that it is necessary to accept a private dimension in this job, but very often the desire to extend one’s training period slows down the aforementioned process. This does not mean and should not be confused with being a lonely, on the other hand, I believe in the power of soloists: to actively look at the path of other colleagues and their experiences in general but at the same time not be too involved in them, to cultivate one’s own dimension.

Info:

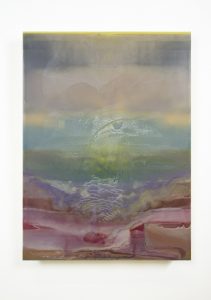

Stefano Cescon, Honey Box Panel #14.20, paraffin, beeswax, oil colors on wooden panel, 43,5 x 31,5 x 6 cm, 2020

Stefano Cescon, Honey Box Panel #14.20, paraffin, beeswax, oil colors on wooden panel, 43,5 x 31,5 x 6 cm, 2020

Stefano Cescon, detail of Honey Boxes. Panel #19.21, paraffin, beeswax, oil colors on wood, 110 × 81 × 5 cm, 2021

Stefano Cescon, detail of Honey Boxes. Panel #19.21, paraffin, beeswax, oil colors on wood, 110 × 81 × 5 cm, 2021

Stefano Cescon, Honey Boxes. Panel #22.21, paraffin, beeswax, oil colors on wood, 110 × 81 × 5 cm, 2021

Stefano Cescon, Honey Boxes. Panel #22.21, paraffin, beeswax, oil colors on wood, 110 × 81 × 5 cm, 2021

Stefano Cescon, Fuoco Fatuo, paraffin, beeswax, oil colors on wood, 29,5 × 22 × 5,5 cm, 2021

Stefano Cescon, Fuoco Fatuo, paraffin, beeswax, oil colors on wood, 29,5 × 22 × 5,5 cm, 2021

For all the images: courtesy the artist and Cramum

Graduated in art history at DAMS in Bologna, city where she continued to live and work, she specialized in Siena with Enrico Crispolti. Curious and attentive to the becoming of the contemporary, she believes in the power of art to make life more interesting and she loves to explore its latest trends through dialogue with artists, curators and gallery owners. She considers writing a form of reasoning and analysis that reconstructs the connection between the artist’s creative path and the surrounding context.

NO COMMENT