With the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the distinction between democratic countries seems to have become more decisive than ever for the destiny of humanity. However, the distinction is not so clear-cut. Even supposedly undemocratic countries, for example, maintain excellent relations with democratic ones, if useful for their strategies. On the other hand, since the beginning of the third millennium there have been authoritative political scientists (such as Colin Crouch) who speak of our era as a post-democratic era, given the innumerable and serious dysfunctions that beset democratic regimes themselves. And what about art? For contemporary art, does it make sense to distinguish works and authors from democratic countries from works and authors from countries deemed non-democratic? This is the question we tried to ask us by visiting one of the most appropriate occasions to explore the situation of contemporary visual art worldwide: the Venice Biennale. Well aware of the enormous scope of our question, we did not pretend to find an immediate answer, but we gathered ideas to keep on wandering. But a Biennale is… a Biennale! One might add: expecially if it is titled as this time: The milk of dreams! That would be to say a dimension so rich in sensory and intellectual stimuli, that no matter how happy, uncertain or sad they are, they make any synthesis, even if only impressionistic, useless. And yet each edition leaves a sense, an aftertaste, an overall and individual leitmotiv. This time, wanting to venture on this still slippery ground, it seems appropriate to dare an adjective: primordial. A “primordial” made of references to the earth, the animal, the plant, the controversies over technological invasiveness, the absence of the human, the maternal generative, the more traditional ethnic roots: all this as a convergence of many works seen in the Biennale. As if contemporary art no longer wanted to trust that actualistic chase of data and information that saturate our present almost to the point of suffocation. As if contemporary art were looking for the first source of inspiration in the foundations of the environment we come from and in which we live. A sort of widespread and shared ecologism, therefore, but rethought, re-imagined, relived, repainted in its most hidden dimensions. But if this notation is valid – and it is clear: it is not certain, given the boundless breadth of the insights that attendance at this Biennale can provide -, is it valid to the point of overcoming the distinction that interests us most here, that of authors working in democratic countries and authors operating in undemocratic countries? If this were the case and if we knew how to read the consequences not from “conflict between civilizations”, but from humanities, a message of hope would emerge. That in any political regime the same albeit vague tendency in the sensitivity and understanding of the artists would be identifiable. A sensitivity and an understanding that in any case would represent and make pertinent the simple and banal fact, but with very complicated reverberations, that there is one humanity, and only one. And therefore universal peace, not wars, should be its sovereign condition.

Now this is precisely the idea that came in our minds after rethinking what our visits to the pavilions of Saudi Arabia, Azerbaijan, China, Egypt, United Arab Emirates, Kazakhstan, Kirgyzstan and Oman left us[1]. In the Saudi Arabia pavilion, curated by Reem Fadda, a single gigantic and monolithic work made of organic material, but supported by a mechanical structure, is exhibited. Its author is Muhannad Shono, an artist particularly sensitive to the problem of life cycles and the power of rebirth in them always operating. The installation representes a sort of monumental tree, almost overhanging the exhibition space in which it is located, but also almost collapsed on one side: suffering and at the same time invasive. A clear symbolization of the vain contemporary attempt to enclose nature, even at the cost of sufferings that inevitably become ours too, if we are not able to appreciate its energy and beauty, in turn evoked by the sensual and welcoming sumptuousness of the “tree” of Shono.

In the Azerbaijan pavilion, on the other hand, the authors are many and all women; Zhuk, Infinity, Ramina Saadatkhan, Fidan Novruzova, Fidan Akhundova, Sabiha Khankishiyeva, Agdes Baghirzade (curated by Emin Mammadov), seven artists whose collective presence well represents the female spirit of the Biennale desired by the director Cecilia Alemani. Under the general title, Born to Love, the themes that chase each other in this pavilion have to do with something like vital time, Azerbaijani cultural history, the ambiguity of technological modernizations, not least the deleterious effects left on the world by pandemic. But more generally and in the background, the fates that await contemporary art in this current epochal turning point are also evoked and questioned with admirable discretion.

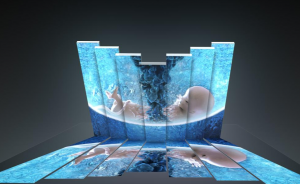

As for China, its pavilion presents works by Liu Jiayu, Wang Yuyang, Xu Lei, AT Group (curated by Zhang Zikang). The title: Meta-Scapes. Inspiring reason: the concept of jing, with all the meanings it has in traditional Chinese literature and which is taken as an interpretative key of the dialectic between humanity, technology and nature. A three-dimensional landscape of mountains artificially reduced to blue-gray symbols by now cold and distant is accompanied by a bulky suspended body of agglomerated scrap metal that could be an aerospace residue and, further away, a tree also raised from the ground, without roots. Further in the corner there is a large set of cut-out shapes, among which the features of a wood made up of plastic and multicolored material are recognizable. Virtues (including aesthetic ones) and the anguish of modernization so much sought after in China thus find their moment of beauty and restless reflection.

Pink supermammels, giants, suspended and swaying at half height welcome us in the Egypt pavilion curated by Mohamed Shoukry. The aesthetically thunderous and almost embarrassing (so much so that the viewer’s walking through its meanders is complex) is an installation by Mohamed Shoukry, Ahmed El Shaer and Weaam El Masry. To be evoked in this way is a promised land, as if it emerged from a pantheistic and ancestral narrative, where milk and honey flow in rivers. But the images projected onto the roundness of these pre-erotic forms give the sense of another dimension, a new technological one, which disturbs or intensifies the dreamlike atmosphere of the whole. If you wish, you could also see even a vague symptom of that today’s al-Sisi Egypt in a dreamlike idyll with the Western democracies in various trades (including those of armaments) and with the rivers of their tourists in search of entertainment, how reluctant to let anyone investigate the murder of our Regeni.

Known for having been a leading figure in that group of “five” artists who in the 1980s constituted the avant-garde of visual art in the United Arab Emirates by importing the first practice of Land Art, Mohamed Ahmed Ibrahim is the author of the works presented in the pavilion of this country, curated by Maya Allisonnel and Mohamed Ahmed Ibrahim. Here color, play and joy seem to be the masters. The single installation that occupies the entire space of the Pavilion offers the viewer a disordered and undulating theory of sculptures between the antrum and the bio-morph. Human bodies or trees? However, here the regime is that of metamorphosis and above all joyful mutations. A figure of light-heartedness and optimism, perhaps favored by the always enviable per capita income boasted by this country, in any case in discreet contrast with the rather pensive and restless climate hovering throughout the rest of the biennial.

The interdisciplinary group called Orta collective (Alexandra Morozova, Rusten Begenov, Darya Jumelya, Alexander Bakanov and Sabina Kuangaliyeva) is the author and curator of the Kazakhstan pavilion. The protagonist and inspirer here is the artist, inventor, writer and “urban madman” Sergey Kalmykov who, despite having inspired generations of artists, died in 1967 in Almaty in a state of total oblivion. Rusty robots, embroidered memory supports, aluminum reflectors and a monumental Circular Generator of Genius made of light and cardboard populate the pavilion recalling the figure of this inspiring character. And it is in his name that scientific and artistic experiments are devised aimed at discovering the Portal of a mysterious fourth dimension. A totally new approach to human creativity is thus simulated. Anyone who remembers the past adhesion of this country to the USSR could thus perhaps glimpse in these performances an amused, anarchic and ironic re-enactment of the ideology of socialist experimentation at the time aimed at the creation of the “new Soviet man”.

In the Kyrkyzstan pavilion, for the first time at the Biennale, located on Giudecca and curated by Janet Rady, Firouz Farman Farmaian presents some of his strong impact paintings. The completely abstract and informal setting, but with an accentuated symbolic tension, aims to evoke the emotions and memories of the exile of the painter born in Iran, when he was still a child he had to flee following the Khomeinist revolution in 1979. This “nomadic dislocation” as Farmaian himself calls it, it led him to investigate the tribal past of his clan, the bonds that have linked him not only to the Kyrgyz culture, but through it to the most ancestral myths of ancient Persia. An introspective journey from which a rediscovery and a fascinating re-presentation of iconic primordial signs emerges

Aisha Stoby is the curator of the Oman pavilion where Anwar Sonja, Hassan Meer, Budoor Al Riyami, Radhika Al Khimji and Raiya Al Rawahi exhibit their works. The title of the ensemble is Destined Imaginaries. On everything else, the figure seems to be an old wise man who appears on a screen inside a capsule where the viewer can watch seated. His disquisitions return to the theme already present elsewhere: the relationship between man and technology. The central question concerns what the former loses of what is most essential to it in relation to the advantages the latter offers. The moral of the story is not lacking. And it is, roughly speaking, an invitation to become aware of the fact that even the highest technology is in any case the creation of man, so that even if the latter finds himself disoriented by the complexity of his discoveries, he can always find inside of himself to deal with.

As a conclusion, it will therefore be left to the motivated reader to establish whether, how much and how the appreciation of similar works and artists operating in undemocratic countries can do without resorting to judgment parameters other than those used for works and artists working in democratic countries.

Valerio Romitelli

[1] See the website https://www.labiennale.org/it/arte/2022/partecipazioni-nazionali from which some information you read here is taken.

Pavilion of Saudi Arabia, Muhannad Shono, The Teaching Tree, 59th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, The Milk of Dreams. Photo by: Andrea Avezzù, courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia

Pavilion of Saudi Arabia, Muhannad Shono, The Teaching Tree, 59th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, The Milk of Dreams. Photo by: Andrea Avezzù, courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia

Pavilion of Azerbaijan, Narmin Israfilova, Born to Love, 2022. Dipinto, installazione. Rendering fotografico di Zhuk (Narmin Israfilova). Courtesy Zhuk (Narmin Israfilova)

Pavilion of Azerbaijan, Narmin Israfilova, Born to Love, 2022. Dipinto, installazione. Rendering fotografico di Zhuk (Narmin Israfilova). Courtesy Zhuk (Narmin Israfilova)

Pavilion of China, Liu Jiayu, Wang Yuyang, Xu Lei, AT Group, META-SCAPE, 59th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, The Milk of Dreams. Photo by: Andrea Avezzù, courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia

Pavilion of China, Liu Jiayu, Wang Yuyang, Xu Lei, AT Group, META-SCAPE, 59th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, The Milk of Dreams. Photo by: Andrea Avezzù, courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia

Pavilion of Egypt, Eden-Like Garden Preserved for the Chosen Ones, 59th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, The Milk of Dreams. Photo by: Marco Cappelletti, courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia

Pavilion of Egypt, Eden-Like Garden Preserved for the Chosen Ones, 59th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, The Milk of Dreams. Photo by: Marco Cappelletti, courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia

Pavilion of United Arab Emirates, Mohamed Ahmed Ibrahim: Between Sunrise and Sunset, 59th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, The Milk of Dreams. Photo by: Andrea Avezzù, courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia

Pavilion of United Arab Emirates, Mohamed Ahmed Ibrahim: Between Sunrise and Sunset, 59th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, The Milk of Dreams. Photo by: Andrea Avezzù, courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia

Pavilion of Kazakhistan, Lai-Phi-Chu-Plee-Lapa, Centre for the New Genius, 59th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, The Milk of Dreams. Photo by: ORTA collective, courtesy e © ORTA collective

Pavilion of Kazakhistan, Lai-Phi-Chu-Plee-Lapa, Centre for the New Genius, 59th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, The Milk of Dreams. Photo by: ORTA collective, courtesy e © ORTA collective

Pavilion of Kyrgyz Republic, Firouz Farman Farmaian, Zero One, sketch of the installation, 2021. Acrylic Marker, White China Ink, White HB Pencil on Black Canson Paper, 75 × 106 cm. Courtesy of the artist

Pavilion of Kyrgyz Republic, Firouz Farman Farmaian, Zero One, sketch of the installation, 2021. Acrylic Marker, White China Ink, White HB Pencil on Black Canson Paper, 75 × 106 cm. Courtesy of the artist

Pavilion of Oman, Destined Imaginaries, 59th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, The Milk of Dreams. Photo by: Camilla Pappagallo per Juliet

Pavilion of Oman, Destined Imaginaries, 59th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, The Milk of Dreams. Photo by: Camilla Pappagallo per Juliet

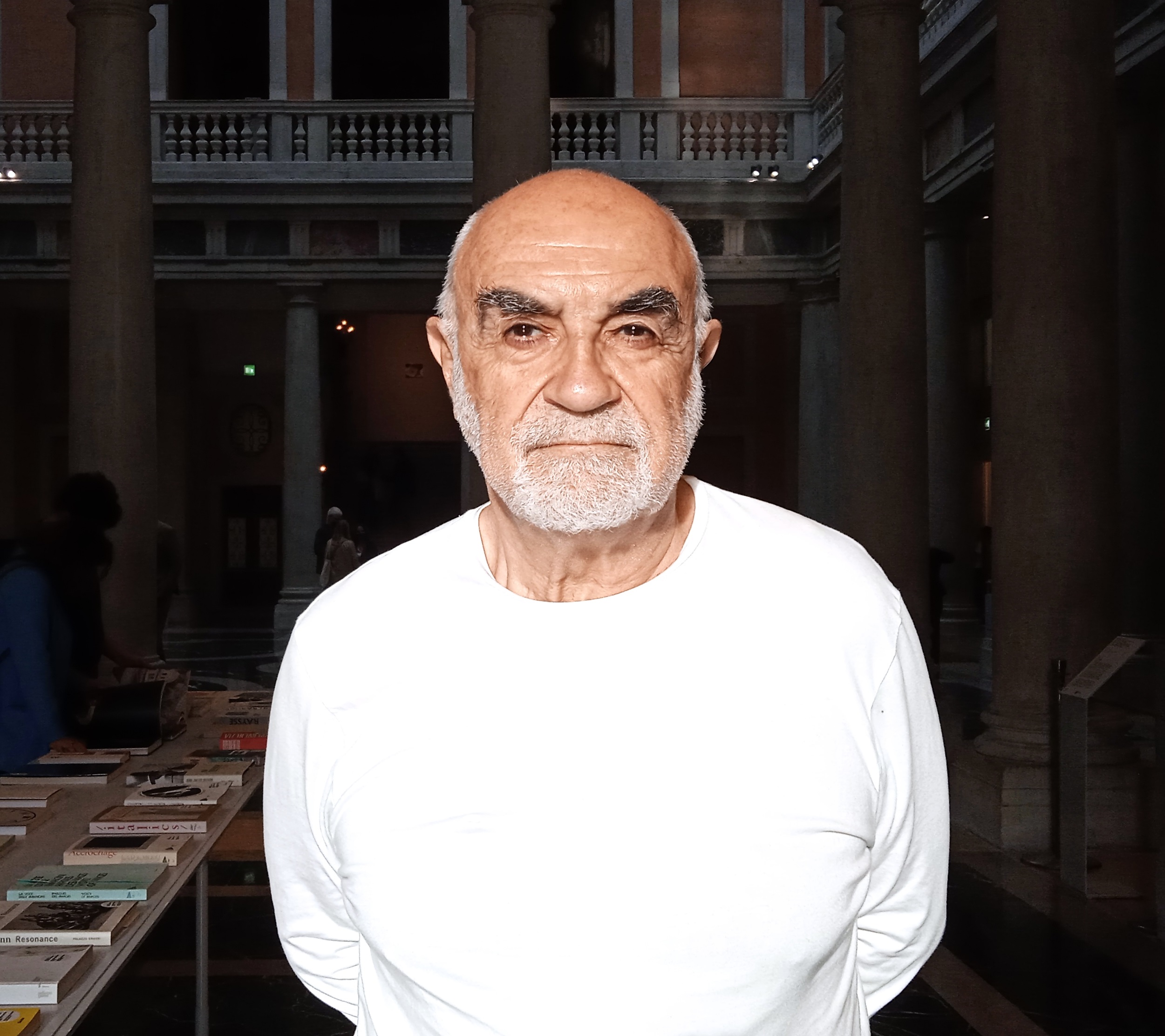

Valerio Romitelli (born in Bologna in 1948) taught, researched and lectured in Italy and abroad. His disciplines: History of political doctrines, History of political movements and parties, Methodology of the social sciences. Among his latest publications: L’amore della politica (2014), La felicità dei partigiani e la nostra (2017), L’enigma dell’Ottobre ‘17 (2017), L’emancipazione a venire. Dopo la fine della storia (2022).

NO COMMENT