For a few years now there have been a rereading and a renewed attention for the experiences made in the social sphere by artists and groups operating in the seventies. Conferences and publications have followed this renewed attention. In particular we recall: L’arte nello spazio urbano. L’esperienza italiana dal 1968 ad oggi by Alessandra Pioselli (Johan & Levi, 2015); La contestazione dell’arte. La pratica artistica verso la vita in area campana da Giuseppe Desiato agli esordi di arte nel sociale by Stefano Taccone (Iod, 2015); Arte fuori dall’arte – esiti degli incontri e scambi fra arti visive e società negli anni Settanta by Cristina Casero, Elena di Raddo, Francesca Gallo (Postmediabooks, 2017); Frameless / l’opera d’arte senza cornice. L’opera d’arte tra supporto, contesto e città by Claudio Musso and Fabiola Naldi (D. Montanari Editore, 2017); Arte in movimento. Gli anni Settanta in Campania by Luca Palermo (Postmediabooks, 2018).

We talk about those years with Annamaria Iodice, an author who was then a leading figure.

What do you remember about Naples in the ‘70s?

Naples was a complex city: bourgeois, popular and sub-proletarian areas lived in close contact and then spread into the industrial areas and the suburbs that flowed into neighbouring villages where, in part, a peasant life still persisted. The awareness of the ecological disaster due to pollution was beginning to be felt and the projects for improvement and rehabilitation of neighbourhoods, still devastated by the war, were trying to establish themselves. In young people there was a desire for a better future and in me there was a desire to find a meaningful path for my and others’ lives also through a new way of making art.

What was your approach to the art world in those years?

I followed the activities of the Guida bookshop (organized by Luca Castellano, Achille Bonito Oliva and other intellectuals); the exhibitions of the Galleria Il Centro; the first events at the Modern Art Agency of Lucio Amelio and the Rassegne di Arte del Mezzogiorno at Palazzo Reale with Pascali and other authors of the Arte Povera movement; Villa Pignatelli with Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg; art-house cinema and innovative theater. We should not however forget the activities of Studio Morra centered on Fluxus and Viennese Actionism and the more minimalist ones of Lia Rumma. Finally Trisorio, the Framart, the Poetry Festivals. The official beginning for the presentation of my work was the invitation that Enrico Crispolti made to the Ambulanti group to take part in the X Rome Quadrennial in 1975.

Can you give us an account on your participation at the 1976 Biennale, Italian Pavilion, in the Social environment section, curated by Enrico Crispolti?

Enrico Crispolti was a militant and anti-system critic. His role had great importance for an unprecedented opening on the horizon of art: a critic who did not judge, did not exercise his power over artists with steered selections, who did not seek sources of income from his commitment and created a relationship between artists and institutions, in search of a new social dimension for art. In the Italian Pavilion, in a multivision hall, all painted in black, designed by Ettore Sottsass, and dedicated to art in the social sphere, slides of the Ambulanti’s work were projected continuously. Our large black and white photo albums were displayed on large tables. In the first ten days of the opening of the exhibition, along with the Ambulanti group, I carried out urban interventions both at the Biennale gardens and in the city. The experience was very lively and interesting, precisely because of the dialogue that took place not only with the citizens, but also with artists such as Joseph Beuys, André Cadere and Mario Merz.

Social environment, how did you mean it, how do you define it?

I thought artists should integrate into society by understanding it more closely and identifying affinities between their own and others’ aspirations. Trying to identify priorities on which to set up one’s cultural activity was necessary as the relationship among studies, artistic interests and society was to be created if one wanted to avoid dependance on the art system and the galleries which was rather limited and based on inscrutable coordinates. By then the artist’s role had become senseless and the avant-gards space was finished. The voice and the work of the artist had to recall the attention on real matters more emerging and contemporary: education and work, personal and cultural wellness, happiness.

1970-2019: can we find a meeting point?

I think that those past issues are today more than ever up to date. Over the following years, many artists worked in that direction. I am thinking, for example, of situations such as the PAV in Torino and Farmacia Wurmkos in Sesto San Giovanni and then of an author such as Ravi Agarwal: in short, these are authors and realities characterized by the territory and the society in which they operate. Furthermore, in 2016, the Turner Prize was awarded to a group of artists, architects and cultural operators involved in the upgrading of a Liverpool district and similar activities were developed in Chicago and Los Angeles. The art involved in social issues (which trespasses into urban planning, design and architecture) is gaining recognition and praise also in London and Paris, as well as in Italy where several projects have been undertaken.

Annamaria Iodice davanti a una sua opera, ph Fabio Rinaldi

Annamaria Iodice davanti a una sua opera, ph Fabio Rinaldi

Annamaria Iodice, Mensolette, 1975

Annamaria Iodice, Mensolette, 1975

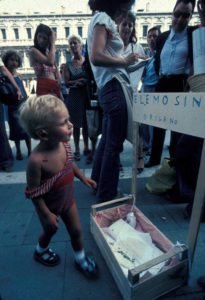

Evento realizzato a Venezia nel 1976, in occasione della partecipazione alla Biennale di Venezia, Padiglione Italia, Ambiente come sociale

Evento realizzato a Venezia nel 1976, in occasione della partecipazione alla Biennale di Venezia, Padiglione Italia, Ambiente come sociale

Annamaria Iodice, Luce dalle stelle, 2010, tecnica mista su tela cm 152 x 200, ph cortesy Parco Foundation

Annamaria Iodice, Luce dalle stelle, 2010, tecnica mista su tela cm 152 x 200, ph cortesy Parco Foundation

He is editorial director of Juliet art magazine.

NO COMMENT