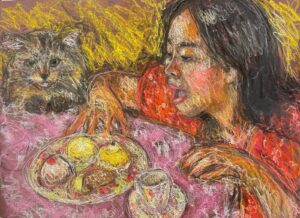

In Caroline Wong’s (1986, Ipoh, Malaysia) work gluttony, the irrepressible craving to swallow on all sorts of food and drink, becomes an ingenious device to distort the stereotypical image of the ideal Asian woman, trapped by social conventionalism. Through the representation of greedy and appetising Dionysian banquets, where order and form are abolished in favour of chaos and excess, the artist investigates without judgement the complex relationships between femininity and food, proposing nourishment as an impulse capable of filling both a physical and emotional void. Wong therefore proposes a counterbalance to the perfect woman – elegant and composed – who abandons all decorum to assume ungainly and uninhibited poses amidst half-rimmed bottles and plates still full of delicacies. The domestic dimension of the family banquet is distorted by an almost stomach-churning hilarity. This effect is amplified by the soft, creamy, consistency of oil pastel which in turn gives the drawings a material, tactile dimension, which instils in the observer a sense of visual satiety. The artist, who recently completed an artistic residency at Castello San Basilio, in Basilicata, where she created a new body of drawings from her ‘Cats and Girls’ series, narrates the rise of a unique, imperfect and hungry modern woman.

Caroline Wong, Spaghetti Lunch, 2023, pastels on paper, 64.5 x 50 cm, courtesy the artist and Castello San Basilio

Mariavittoria Pirera: Let’s start from the beginning: can you tell us about your background? What was your first encounter with art and how this led you to develop your artistic language?

Caroline Wong: I’m of Malaysian-Chinese descent, but grew up in London. I’d say I’ve always been a shy person and as a child I used drawing as a kind of escapism, I drew everything, then during my teenage years I gravitated towards figurative art, particularly portraiture. At the age of eighteen, I hoped to go to art school but was expected to do something more academic and secure. My twenties, in short, was a strange time of doing everything I could to avoid art for fear of upsetting my family. It was only later, after I reached my thirties, that I decided to change things around. By then, I felt I had gathered enough experience and visual information from time spent in Asia and Europe, to forge a practice that was ultimately a ‘form of gleeful rebellion’. My practice is ultimately about women who go against the grain, those who are caught between cultures and who hunger for food, revenge and affection. The frenzy and pleasure depicted carry over into the making of the image so that the act of drawing or painting too becomes a form of greedy, guiltless consumption. What I seek is a kind of beauty in excess.

The women in your drawings are depicted without the decorum and formalism that usually characterises traditional portraiture.

Yes, I found portraiture limiting as it is focused on likeness and flattery. [In contrast] I wanted to make images of women which, though naturalistic and somewhat traditional in execution, conveyed other states of being that were angrier, ecstatic, orgasmic, drunk and unruly. This allowed me to subvert the meirenhua genre in East Asian art. Translated as ‘images of beautiful women’, this is a type of portrait focused on a kind of beauty that’s founded on good conduct, restraint and the withholding of desire. The discipline and patience of these women are further mirrored in the execution which is a slow, painstakingly careful one. So, my images are a rewriting of beauty as an experience of freedom and unadulterated pleasure.

Caroline Wong, Tea Time, 2023, pastels on paper, 64.5 x 50 cm, courtesy the artist and Castello San Basilio

Your works seem to revolve around a ravenous fever, a hunger that never seems to be truly satisfied, despite the quantities of food they continue to ingest. What lies behind this desire to consume, to eat?

The insatiable hunger can take on different significations depending on what I’m going through at the time of the drawing. Often the drawings are motivated by frustration, anxiety, nihilism, lust, desire, and naughtiness. It’s really just ‘eating one’s feelings’ but transferred to drawing.

The sense of fullness is amplified by the use of warm tones that sometimes take on almost iridescent gradations. What role does colour play in your art?

Basically, I like to create images that are delicious to look at, so I tend to treat colours as if they were flavours. I want my work to be seductive in its sweetness, nourishing and comforting like umami[1], perhaps a bit too picante or rich in its boldness. Indeed, I insist on colour being a key ingredient in the images, although, sometime [in the past] it was considered as a feminine and therefore secondary, sometimes corrupting quality in art. Plato [for example] used to deride colour as a mere cosmetic element, as opposed to the line that provided the structure and form of an image. [Again], Impressionist painting was characterised as feminine and sensually decadent because it prized the emotionality and seductiveness of colour and the materiality of paint over the more ‘masculine’ defining qualities of line and composition. In short, I seek to reclaim and enlarge the alluring, seductive, emotional qualities of an image.

Caroline Wong, The Bacchanal, 2023, pastels on paper, 187 x 262 cm, courtesy the artist and Castello San Basilio

Cats preside at banquets, as for instance in the series Cats and Girls. Why the cat and how does it fit into the scheme: woman/food?

In my practice [as hunger] the cat [is not limited to one meaning], but symbolises a multitude of things. I admire the insouciance and independence of cats, the way they prioritise their needs and pleasure over everything else. In fact, they are selfish, amoral creatures and in no way noble or exemplary like dogs or horses. I’m also interested in their feminisation throughout history, [for instance]: the way they have represented the darker and deviant side of women through their link to witchcraft or the way cats have come to represent female sexuality – the invention of the catsuit, the figure of Cat Woman. Similarly, women can be described as feline, catlike, or catty. There is then a whole vocabulary of terms to indicate the promiscuous woman such as ‘alley cat’ or ‘sex kitten’, and of course ‘pussy’. Basically, the cat is a symbol of female rebellion and non-conformity, a reclamation of female pleasure in all its perversity.

Speaking of cats and Cats and Girls series, during your residency at Castello San Basilio you created new works from the series. Would you like to tell us something about these?

Sure, I worked on three smaller drawings and one very large one. These [The Time, Midnight Supper, Spaghetti Lung and The Bacchanal] focus on the food I ate during my time in residency—in restaurants or meals that were prepared for me in the castle. In the works therefore you can see posts of spaghetti, plates of ham and melon, bowls of fruit and even local cakes etc. The smaller works are more intimate and portray an individual character lusting over or biting into food. It’s a slower and more detailed type of drawing, almost like savouring a moment. The largest work is a group composition entitled The Bacchanal, and it recalls the ancient orgiastic banquets depicted in art history. [Unlike the others], the latter offers a more noisy, more chaotic, frenzied, bodily drawing experience. It’s pure catharsis for me.

Caroline Wong, Midnight Supper, 2023, pastels on paper, 93 x 70 cm, courtesy the artist and Castello San Basilio

Often when we talk about art residencies we pay more attention to the selection parameters of the directors, than to those of the artists. What are the criteria for accepting or not an invitation to participate? What do you look for in a residency?

I suppose that it’s necessary to have a good feeling about the director of the residency, with whom it must be easy to work. They must also be transparent both in what they offer me and what they expect from me. Also, [I pay attention to the number of works I am asked for], in fact, I don’t want to be under pressure to churn out a flood of works or to be told how to do them. As for the location, I like to think I’m quite flexible with regards to where I do a residency. Finally, the residency also has to support or resonate with the aims of my own practice. Italy for me is an ideal place for a residency because I feel people here know how to enjoy life.

[1] https://it.umamiinfo.com/what/whatisumami/

Info:

Mariavittoria Pirera, born in 1995, has a historical-artistic education obtained with a three-year degree in History of Cultural Heritage, historical-artistic profile, at Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milan, and with a master’s degree in History and Conservation of artistic heritage, contemporary art history, at Ca’ Foscari University, Venice. She lives and works in Milan.

NO COMMENT