Photojournalism is changing. Social media impose times and ways that ask to rethink the relationship with reality and with the viewer. In the revolution of rules and forms, ethics, respect and morals remain an essential baggage with which to cross the border towards new media. On the threshold, with one foot rooted in the history of reportage and the other in the new that advances, there is also Dario Mitidieri: an avalanche of prizes won and acknowledgments among the most prestigious in the world. Yet his photography today has to confront Instagram. Art, however, cannot be improvised and the difference between amateur and professional passes precisely through the history that Mitidieri has built. The occasion of his return to Italy thanks to the Sudest57 agency that will take him to Verona in September at the Grenze Photography Festival, has become a chat about the profession of the photographer between romance and new challenges.

Simone Azzoni: “I am interested in man and his life so short, so fragile, so threatened”. I hear this phrase from Bresson as a guide, a key to understanding your work …. What interests you about man? What edges of humanity are you interested in lifting? What does your “humanist” mission consist of?

Dario Mitidieri: I am interested in the fragility of man, the complexity of the person and diversity. My main mission was – where I could – to give light where there was darkness, to give a voice to those who did not have it and to show what – like the Tiananmen Square project – that no one would ever see. My curiosity towards people, seeing what is around the corner has become a profession.

I feel an interesting balance between empathy, dramatic participation in situations and the need to act within a social, historical mission, transversal to your projects. How do you build this balance?

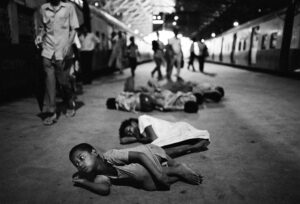

Balance is an important thing. Either you have it inside or you don’t have it. Empathy and sensitivity are essential. My way of being reflects my way of photographing. I consider myself a sensitive person. What matters is respect. If I had no respect for people I would not have been able to photograph the Children of Bombay. Respect is the most important thing.

Another element that I feel constant is great care, delicacy, attention to others, suspension of judgment. Are these professional attitudes still practicable today, in an era of iconographic violence and search for scandal?

Today you have to pay attention to what to photograph, how you photograph and also what you say. In a social media context where everything is shared, it is necessary to evaluate the impact of the image on other people. I have never photographed violence itself. Faced with the tsunami that devastated Bangladesh, I chose to immortalize an elderly man with two baskets of water on his shoulders. Behind him a pile of corpses, but out of focus. That photo went around the world. Violence is not needed.

“What right do I have to represent you?” Each time this question by Levi could have a negotiation answer. What’s yours? Is there a compromise between being a spectator and being an intruder?

I still ask myself after thirty-five years of work. The trade-off is the need to document a reality in order to do good to other people, even if this can mean photographing people who don’t want to be photographed. In Bombay I photographed pedophiles for example, they saw me as one of them and let themselves be photographed but I did it because it was important to tell that reality. The right to represent can be very subtle and sometimes that border is crossed. Sometimes I photograph without asking, but then there is the dialogue. And it is the other who sets the limit. The photographer must first of all be a person.

Is there a right preparation time before starting to shoot? How much time do you give yourself to know the reality you will tell?

The quality of a shot doesn’t necessarily depend on the preparation time. It all depends on the moment and the story itself. There are times when the preparation does not exist or has a short time frame. In some cases the research is reduced to a strategy, to a quick planning to get to the place and situation that I have decided to photograph. I did a work on charismatic evangelism in the world, preparation was needed there. But for example, in Tiananmen Square, the preparation consisted of finding an escape route in case they started shooting. In Iraq I had planned the trip only as far as the border, without knowing how I would enter the country.

What criterion drives the choice of black and white or color? To this same question, Monika Bulaj and Francesco Cito replied that there is no real criterion, rather a “feeling” …

I agree. By feeling I mean a subjective approach. As far as I’m concerned, there is also a historical context to consider. During my career, at the beginning I photographed almost exclusively in black and white. I was fascinated by the photographers of Magnum Photos, but sometimes even then I felt the need to photograph in color. For example, the report on the tsunami was made with a panoramic Hasselblad to show the vastness. Until the advent of digital I was shooting in black and white, after we have all become “lazy” as they say here in London. You go drowsy with digital. The photos of the Syrian refugees were shot in color but they weren’t strong enough and I put them in black and white and the work became more powerful, more human, more sensitive, more of a classic reportage job. I was born in the era when the classic reportage was in black and white and that choice formed me and I identified with it.

I believe that in some situations the urgency to tell a story or to fix an important moment in history has prevailed (for example in the Tienanmen project) … How to safeguard and distinguish in these cases the “artistic coefficient” that photography must protect and make explicit?

In the case of Tienanmen the urge to tell was more important than the aesthetic one. It’s one of those moments when your visceral passion takes a back seat. The most important thing is to document: a repression that a government would have denied if there had not been our testimonies. But even on these extreme occasions the difference between professional and amateur is clear. The professional has the instinct, the ability to be at the right time in the right place, goes automatically and composes without thinking. And then the difference is training, when I was young I spent a lot of money to buy photographic magazines, I fed on thousands of images.

Shock or change? What is the purpose of a photojournalist today, with the competition of social media that burn the situations too succinctly?

You produce a change, but the change is also produced by shocking. If I hadn’t taken a photo of the pile of dead in a hospital in Thiennamen Square, I wouldn’t have gotten attention. How do you make people realize how many students have been killed if you don’t show them? A photograph is worth many words. The change is now made with social media.

It is the social media that seem to deprive the image of the time it takes to meditate on it … what do you think about it?

Visiting an exhibition or reading a book are fundamental experiences. It’s nice to have something to touch and feel. We look at hundreds of images every day. The strength of social media, however, is also to amplify a photo. And make something known.

Is post-production, the technical artifice – Photoshop – to be demonized? Is there a good use of it that safeguards the truth of the shot?

Nobody can stop you from being creative, no matter how. Retouching in different ways has always existed. It is necessary to differentiate the creative use from the visual. In a journalistic context, reality cannot be altered. Photoshop is a great companion for creating images that are impossible to make. Photography can be a documentary process but also a creative and personal one. Software is welcome: it has always been used in the art world.

We are passionate about stories… Does telling them through photography still make sense, despite the fact that newspapers buy fewer of them than in the past?

This is our cross. The way of telling the story or reading it hasn’t changed, we always have the curiosity to listen, read and we photographers need to photograph but there is no more money. I did stuff that was published in crazy money magazines that didn’t pay photographers. When I ask a newspaper to get paid it’s like I’m from another planet. They offer me a few pennies that barely cover the cost of a plane. I bow to emerging and less emerging photographers who produce insane works that are published for little money.

London is an observatory from which to look at Italian photography today… What do you think, where are we?

A change is taking place that leaves me amazed, I discovered many photographers on Instagram. They published reports that nobody else would publish: social networks are more important than paper. What works today? In my opinion a mix of conceptual, social and Photoshop.

What did you do during the pandemic?

I focused on personal projects that have to do with Covid, on my family, I photographed it every day. Every day I documented my area of London and posted on Instagram. And every day was important, a way to stay creative in one of the most difficult years of our life.

Info:

Dario Mitidieri, Street children from the Victoria Terminus (VT) gang waking up on platform 7 at Victoria Terminus (VT) station in Bombay, India © Dario Mitidieri 1992, courtesy the artist

Dario Mitidieri, Street children from the Victoria Terminus (VT) gang waking up on platform 7 at Victoria Terminus (VT) station in Bombay, India © Dario Mitidieri 1992, courtesy the artist

Dario Mitidieri, Savita, a 2 and a half year old girl from north Bombay, performs for Arab tourists near the Gate Way of India in Colaba. Bombay, India © Dario Mitidieri 1992, courtesy the artist

Dario Mitidieri, Savita, a 2 and a half year old girl from north Bombay, performs for Arab tourists near the Gate Way of India in Colaba. Bombay, India © Dario Mitidieri 1992, courtesy the artist

Dario Mitidieri, After a police round-up, Sabina (9 years old) and her sister Nafisa (4 years old) from Aurangabad, wait in a police cell at Dadar train station. They were later taken to Dongry Children’s Remand Home in Bombay, India © Dario Mitidieri 1992, courtesy the artist

Dario Mitidieri, After a police round-up, Sabina (9 years old) and her sister Nafisa (4 years old) from Aurangabad, wait in a police cell at Dadar train station. They were later taken to Dongry Children’s Remand Home in Bombay, India © Dario Mitidieri 1992, courtesy the artist

Dario Mitidieri, Bombay, India © Dario Mitidieri 1992, courtesy the artist

Dario Mitidieri, Bombay, India © Dario Mitidieri 1992, courtesy the artist

Dario Mitidieri, Bombay, India © Dario Mitidieri 1992, courtesy the artist

Dario Mitidieri, Bombay, India © Dario Mitidieri 1992, courtesy the artist

Dario Mitidieri, Bombay, India © Dario Mitidieri 1992, courtesy the artist

Dario Mitidieri, Bombay, India © Dario Mitidieri 1992, courtesy the artist

He is an art critic and professor of Contemporary Art History at IUSVE. He also teaches Critical Image Reading at the Palladio Institute of Design in Verona and Contemporary Art at the Master of Publishing at the University of Verona. He has curated several contemporary art exhibitions in unconventional places. He is the artistic director of the Grenze Photography Festival. He is a theater critic for national magazines and newspapers. He organizes research and experimentation theatrical events. Among the recent publications Frame – Videoarte e dintorni for the University Library, Lo Sguardo della Gallina for Lazy Dog Editions and for Mimemsis Smagliature in 2018 and 2021 for the same publishing house, Theater and photography.

NO COMMENT