Since June 2017 I am carrying out a serial research for the print edition of Juliet Art Magazine on new technologies and the imaginative possibilities of the creative artists on the future, with the participation of Italian and foreign personalities, representative of various disciplinary fields. Here is the interview with the art critic and curator Domenico Quaranta, who is also an expert author of essays on the most advanced technological media.

Luciano Marucci: Are new technologies able to stimulate imagination and foster artistic inventions?

Domenico Quaranta: Of course, they are. New technologies feed on our imagination and influence it by creating new ways of communicating, giving rise to new aesthetics and new relational spaces. If we consider virtual reality, which is recently experiencing a further revival (and a further hype): it translates into immersive environments and imaginary narrative spaces shaped by literature and the cinema of the 80s and 90s – from Neuromancer by William Gibson to Brainstorm by Douglas Trumbull – but at its current level of technological development, it allows to experiment with a wide spectrum of aesthetics (from photorealism to abstraction), of possible relationships between the virtual space and the surrounding reality, between the virtual space and the spectator, and between the viewer and other participants. It allows, in other words, to create new imaginary scenarios. As a matter of fact, as new technologies are able to stimulate imagination and invention, they can also inhibit them, pushing the artists to ask troublesome questions, such as: What space is left for me? How much does the medium influence me and how much creative freedom does it leave me? How can I carve out a role in this infinite flow of information, in this condition of diffused creativity?

However, I believe that these questions can also be productive, as a stimulus to a critical relationship with information technologies.

Is creativity, through digital tools, also stimulated by the socio-cultural context?

Information technologies are an integral part of our current socio-cultural context, and in part they shape and influence it. We can observe it in every area of social life: from politics to economy, to the forms of socialization and communication. It is quite obvious that the impact of certain themes and tools on cultural debate and on everyday life generates a common cultural fabric on which an artist can work, and the widespread use of certain instruments and devices can open a space for intervention and dialogue with a potential audience, not necessarily mediated by traditional art infrastructures such as galleries, art fairs and museums.

Do the visual artists of the new generation tend to exploit the potential of advanced technologies?

It depends on what is meant by “advanced technologies”. The recent history of art teaches us that a new medium establishes itself as an artistic medium when it becomes economically and operationally accessible. Contemporary art does not entirely reject, but has an idiosyncrasy towards “know-how”, the acquisition of a technical expertise as a prerequisite and a condition for the use of a medium, as well as the “media specificity”. It is afraid it will be diverted from problems of a more conceptual nature, and be reduced to simple craftsmanship. It is afraid of becoming a slave to the medium, instrumental to the simple explication of its potential. The basic assumption of art in the Post-Medium Era is that you do not necessarily need to have gained professional use of a means to use it, and to be an artist you must avoid, as much as possible, to constrain your artistic practice to a single medium or language; you do not have to be a skilled photographer to do photography, you do not have to be a skilled videomaker to make videos, and you do not have to be an engineer to use a computer. Each of these means has been recognized as a legitimate artistic medium when it has satisfied these conditions. At this point, the acquisition of a technical skill is no longer a constraint, but becomes a choice of freedom, as that of focusing on a single medium. Highly advanced technologies impose a level of training and a focus which monopolize our ideas and distract us from exploring other possibilities. Artists of all times have been attracted to them, but when they took up the challenge, they did it accepting the risk of being marginalized by the art world of their time: think of the computer artists of the 70s. The acceptance of digital technologies in the contemporary art world has gone hand in hand with the explosion of consumer technology, “cheap and easy to use”. But if we think that a smartphone has computing power and memory capabilities more powerful than the computers that brought man to the moon, we can certainly consider today’s consumer technologies as “advanced technologies”.

What is the most updated role of the new technological media?

Well, to save the world which they themselves have contributed to bring to the verge of collapse.

Will the post-digital condition regenerate a more ‘humane’ reality?

This is a very interesting question. In the 80s and 90s, all the narrative on new information technologies was based on the description of the latter as “another” dimension compared to reality. Cyberspace, the notion of virtual, the idea of the Internet as a new frontier (like space in the 60s); all these aim at highlighting this otherness. During the past two decades, with the penetration of consumer technologies in everyday life, this perception of “otherness compared to reality” has faded: the “digital” is no longer experienced as something other than the real, but as a dimension of reality – which in some ways precedes it, influences it, shapes it. The post-digital, which describes the material manifestations of the digital, is the translation into visual metaphors of this change in perception. Rather than creating a more humane reality, it forces us to review the idea that technologies are inhumane. After all, what is innate human nature if not our tendency to build “extensions of ourselves”, as Marshall McLuhan defines the media? More than any evolutionary change, in the posture or in the dimensions of the brain, it was this step – the use of stones as weapons, of animal skins as clothes, the invention of the wheel and the control of fire – to distinguish us definitively from the animal world.

Is the artistic production fostered by the Web’s role of socializing?

As everything else in the world, the social web can be an inspiration or a tool for art. And as a communication tool, it can provide artists with a useful means of conveying their work through their network, and submitting it to the public. Actually, now that well-known and renowned artists like Richard Prince, Maurizio Cattelan, Cindy Sherman, Damien Hirst or Nan Goldin have begun to make an intensive use of social networks, what I have just said almost sounds like obviousness, even if it was not so until a few years ago. But as I have already pointed out, the excess of information and images, the effect of trivialization generated by the standardization of formats and the infinite scrolling, can also be experienced in reverse, and become a disincentive to intervene creatively in this horde of signals that inevitably turns into white noise.

Do digital applications have a significant influence on display formats?

Yes, and from different points of view. I often show my students the first episode of Ways of Seeing (1972), the phenomenal documentary by John Berger on how technical reproducibility and transmission of images are changing the way we see. It is interesting to note that having a smartphone perpetually in your pocket inevitably sabotages the aesthetic experience: it interrupts the continuity, subtracts attention, makes the use of those images that Berger describes as “silent, still” dynamic and noisy. The artwork becomes a distraction during a conversation, the occasion of a photo or a selfie, the input for a search for information. We can hardly manage to live the artwork without information, be it provided by a caption or an audio guide. Our devices are the trolls of aesthetic experience. The traditional exhibition formats are inadequate to capture the attention of the distracted contemporary wanderer, and they mostly survive in places of socialization and fast aesthetic consumption, such as fairs, and in museums unable to renew themselves. Spectacle and experience become the new keywords, a drift not necessarily negative and readable at all levels, from the performances of Tino Sehgal to immersive installations, from Art Unlimited to video mapping to multimedia exhibitions. If you believe that huge projections, interactivity and different sensory inputs are the best way to bring artists like Caravaggio or Van Gogh to the general public, it means that you have lost all confidence in direct enjoyment of the artwork.

March 17th, 2018

(Translated by Serena Fioravanti)

curated by Luciano Marucci

Domenico Quaranta (ph Michela De Carlo)

Domenico Quaranta (ph Michela De Carlo)

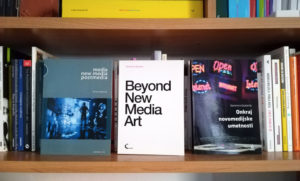

Domenico Quaranta,“Media New Media Postmedia” (postmediabooks, 2010). On the right English (Link Editions, 2013) and Slovenian (Aksioma, 2014) versions (courtesy the Author)

Domenico Quaranta,“Media New Media Postmedia” (postmediabooks, 2010). On the right English (Link Editions, 2013) and Slovenian (Aksioma, 2014) versions (courtesy the Author)

Gazira Babeli, “Acting as Aliens”, 2009, Kapelica (Ljubliana), performance produced by Aksioma, curated by Domenico Quaranta (ph Miha Fras)

Gazira Babeli, “Acting as Aliens”, 2009, Kapelica (Ljubliana), performance produced by Aksioma, curated by Domenico Quaranta (ph Miha Fras)

Thomson & Craighead, “Unprepared Piano”, 2009, installation showed in the section “Expanded Box”, Arco Art Fair, Madrid, February 2009, curated by Domenico Quaranta (courtesy D. Quaranta)

Thomson & Craighead, “Unprepared Piano”, 2009, installation showed in the section “Expanded Box”, Arco Art Fair, Madrid, February 2009, curated by Domenico Quaranta (courtesy D. Quaranta)

Ryan Trecartin, “Roamie View: History Enhancement”, 2009-2010. HD Video, installation in “Collect the World. The Artist as Archivist in the Internet Age”, HeK (Haus der Elektronischen Künste), Basel 2012, curated by Domenico Quaranta (courtesy D. Quaranta).

Ryan Trecartin, “Roamie View: History Enhancement”, 2009-2010. HD Video, installation in “Collect the World. The Artist as Archivist in the Internet Age”, HeK (Haus der Elektronischen Künste), Basel 2012, curated by Domenico Quaranta (courtesy D. Quaranta).

Rafael Rozendaal, “Falling Falling .com”, 2011, website, installation in “Mankind / Machinekind”, Krinzinger Projekte, Vienna 2015, curated by Domenico Quaranta (courtesy D. Quaranta)

Rafael Rozendaal, “Falling Falling .com”, 2011, website, installation in “Mankind / Machinekind”, Krinzinger Projekte, Vienna 2015, curated by Domenico Quaranta (courtesy D. Quaranta)

Peter Sunde, “Kopimashin”, 2015, installation in “Escaping the Digital Unease” 2017, Kunsthaus Langenthal (Suisse), curated by Raffael Doerig, Domenico Quaranta e Fabio Paris (courtesy D. Quaranta; ph Raffael Doerig)

Peter Sunde, “Kopimashin”, 2015, installation in “Escaping the Digital Unease” 2017, Kunsthaus Langenthal (Suisse), curated by Raffael Doerig, Domenico Quaranta e Fabio Paris (courtesy D. Quaranta; ph Raffael Doerig)

I’m Luciano Marucci, born by case in Arezzo and I look my age… After a period in which I dedicated myself to journalism, applied ecology, environmental education and traveling the world, I occasionally collaborated as an art critic with specialized magazines (“Flash Art”, “Arte & Critica”, “Segno”, “Hortus”, “Ali”) and with varied cultural periodicals. Since 1991 in “Juliet” art magazine (in print and edition) I have regularly been publishing extensive services on interdisciplinary topics (involving important personalities), reportages of international events, reviews of exhibitions. I have edited monographic studies on contemporary artists and book-interviews. As an independent curator I have curated individual and collective exhibitions in institutional and telematic spaces. I live in Ascoli Piceno.

NO COMMENT