When a mountain peak turns upside down or a body of water becomes a place of connection between the sky and the earth, also upside down, the gaze seems to take a path without predefined indications. However in the fourteen photographs from the series “Pipelines Across Permafrost” (2020) the imagination of Mary Mattingly, a Brooklyn-based artist born in 1978, has nothing dreamlike, and the provocation is not limited to a temporary disturbance of the observer – you do not know where to start looking – but wants to talk about a time beyond human duration: the time of the Earth.

In “Pipelines Across Permafrost” each image is a sequence that tells the story of the place represented: a complex story, therefore, that the artist returns directly using the technique of assembly. Each photograph is the result of a stratification in which several images alchemically join in a fluid timeline. Here the center and the vanishing point are missing, because every place escapes from the postcard aesthetics and is returned in its geological scope: Mattingly’s aims are in fact to go beyond the simple documentation, to try to insert the duration in the space of the image, and above all to witness how forced anthropization can cause drastic accelerations in the natural rhythms of the Earth. Looking at these photographs one perceives how nature is now in an intermediate position: strong because of the power of a still not human time and at the same time fragile in relation to all those current ideologies that consider it as passive extraction ground: an example of this short-circuit is ‘Pipelines Crossing Permafrost’, in which, adopting an upward point of view, the artist seems to create a continuity between the line of a split of the Alaska Arctic cap and the silhouette of an oil pipeline. Two signs, inserted in the rigid verticality of a single image, in front of which the observer is driven to adopt a holistic vision that strays both from an absolute protagonism of nature, both from an explicit denunciation of the extracivist ideology in the Anthropocene era.

The artist remains in this interlude, keeping on a purely visual discourse in which photography stratifies in the same way as the Earth on which it rests its lens: geological image that speaks of a deep time. The rest of the series is also born from this subtle provocation in which nature always shows itself to be plural and plastic according to temporal rhythms impossible to perimeter. Once this complexity is enclosed in the space of the image, it makes itself accessible, and projects the encounter with the observer elsewhere far from the actual present. So this shift allows us to move away both from the immediacy of a photographic report, and from the lyricism of a travel diary, to position ourselves on a broader perspective: an unprecedented perception toward which Mattingly invites without any final judgment, and in which is enclosed all the political value of “Pipelines Across Permafrost”. In times where the narratives of irreversible catastrophe and the directionless present prevail, Mary Mattingly opens a critical confrontation with what geologist and writer Marcia Bjornerud defines as ‘infantile indifference and partial disbelief about the time before our appearance on Earth’.

The artist’s provocation is silent, therefore, all resolved at a perceptive level, at the moment when the gaze is disoriented as it embraces the fullness of the Earth it inhabits, discovering itself as an actor in a thousand-year history. The artist suggests this new perspective that goes beyond modern temporality, and dedicates these photographs to those people who have made this awareness a clear political voice aimed at protecting the represented places. Considering again the photograph taken as example, ‘Pipelines Crossing Permafrost’, the title is completed with the following formula: “For Neetsa’ii Gwich’in elder Sarah James and the fight against oil development in Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge”; and so it applies to all the other photographs in the series. Yet another expression of the bond that unites the human being to the Earth, now expressed in the light of future hope, with a dedication to those who mobilize so that that deep time in which we are all immersed does not radically change its rhythms that have always ensured life continuity on our planet. Mary Mattingly’s geological images are stories of awareness and hope: a new perspective in which the language of art uses its codes to talk about climate justice and protection of the planet, as long as the gaze agrees to get lost, even for a little while, in the fullness of that time that has always lived, and of which he seems to have forgotten.

Info:

Mary Mattingly (Da sinistra a destra), The Gualcarque River, 2020. Chromogenic dye coupler print, 72 x 18 inches. For Berta Cáceres, her daughter, and their work continuing the fight against the Agua Zarca dam along the Gualcarque River in western Honduras on teritory inhabited by the indigenous Lenca Peoples; A Controlled Burn, 2020. Chromogenic dye coupler print, 60 x 18 inches. For the stewards of traditional ecological knowledge that have worked for generations promoting healthy forest growth with controlled fire application; Rematriation, 2020. Chromogenic dye coupler print, 72 x 18 inches. For the Green Belt Movement, led by Nobel Peace Prize winner Wangari Maathai. Maathai received the Nobel for leading an effort to plant 30 million trees in Africa, that has led people to do similar work around the world. © Mary Mattingly, Courtesy Robert Mann Gallery

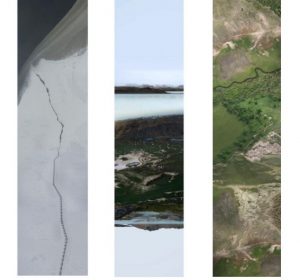

Mary Mattingly (Da sinistra a destra), Pipelines Crossing Permafrost, 2020, Chromogenic dye coupler print 44 x 14 inches, For Neetsa’ii Gwich’in elder Sarah James and the fight against oil development in Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge; Remediating El Cerrejon, 2020, Chromogenic dye coupler print 52 x 14 inches, For Jakeline Romero who works towards environmental justice and clean water in Columbia in an ongoing struggle against El Cerrejon, the largest open-pit mine for thousands of miles; The Lookout, 2020, Chromogenic dye coupler print, 72 x 18 inches, For José Isidro Tendetza Antún, Shuar leader and Ecuadorean activist who fought against El Mirador, the gold and copper mine sited on southern Amazon rainforest lands belonging to the Shuar Peoples. The mine is projected to destroy around 450,000 acres of rainforest. © Mary Mattingly, Courtesy Robert Mann Gallery

Mary Mattingly (Da sinistra a destra), Pipelines Crossing Permafrost, 2020, Chromogenic dye coupler print 44 x 14 inches, For Neetsa’ii Gwich’in elder Sarah James and the fight against oil development in Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge; Remediating El Cerrejon, 2020, Chromogenic dye coupler print 52 x 14 inches, For Jakeline Romero who works towards environmental justice and clean water in Columbia in an ongoing struggle against El Cerrejon, the largest open-pit mine for thousands of miles; The Lookout, 2020, Chromogenic dye coupler print, 72 x 18 inches, For José Isidro Tendetza Antún, Shuar leader and Ecuadorean activist who fought against El Mirador, the gold and copper mine sited on southern Amazon rainforest lands belonging to the Shuar Peoples. The mine is projected to destroy around 450,000 acres of rainforest. © Mary Mattingly, Courtesy Robert Mann Gallery

Piermario De Angelis was born in Pescara on 06/10/1997. After graduating from high school he moved to Milan to attend the three-year degree course in Arts, Design and Entertainment at the IULM university. He is currently a second year student of the two-year course of Visual Cultures and Curatorial Practices at the Brera Academy of Fine Arts. He is a contributor for ‘Juliet Art Magazine’ and ‘Kabul Magazine’. In 2021 he co-founded, together with other students of the Brera Academy, the non-profit cultural association Genealogie Del Futuro: a reality that addresses socio-political and environmental issues through alternative community building practices, through an artistic and curatorial perspective. His research aims to be an exploration of the critical potential of art and images in relation to the urgencies of contemporaneity.

NO COMMENT