Perfectionist. Obsessive. Genius. No other filmmaker has embodied the idea of film director as demiurge better than Stanley Kubrick (1928-1999): a builder of works governed by the idea of perfection, inside which everything human conceals the potential for the chaotic. A revolutionary creator of forms, Kubrick explored several genres and conceived each of his films as a cathedral-like architecture in which to lose oneself in the search for hidden meaning and revealing details. His painstaking construction of himself as a character – remote, elusive and cerebral – cannot be extricated from a creative discourse that explored the possibilities of film as an essentially visual means of expression, as close to the universality of the language of symbols as it is remote from the dangers of the discursive. In his imaginery, the icy formalistic rigour of symmetries contrasts with a pessimistic yet hugely compassionate view of humankind underpinned by the constant themes of violence, desire, obsession and death drive.

Stanley Kubrick was one of the most influential filmmakers of the 20th century and left us a legacy of 16 films that have not exhausted their potential fr interpretation, academic analysis and mytologizing passion. From the mathematical precision of The Killing to the dreamlike labyrints of Eyes Wide Shut, his films expanded the expressive potential of genres., challenging the taboos of reperesentation with a persistence that always eschewed the superficiality of the simple dramatic effect. A filmmaker of spaces – the corridor of the Overlook Hotel, the trenches in Paths of Glory, the war room in Dr. Strangelove -, characters, and situations – the Ludovico Technique in AClockwork Orange, the training/brainwashing session in Full Metal Jacket – Stanley Kubrick transformed his work into a powerful intelletual and artistic challenge touched by a peculiar gift for timelessness.

Kubrick compared the filmmaking process to trying to write War and Peace in a bumper car at an amusement park. “When you finally geti t right, there are not many joys in life that can equal the feeling” he said. After attaining the longed-for privilege of complete artistic independance, Stanley Kubrik was able to channel his obsession for absolute control of the creative process, an urge that led him to master every stage of the filmmaking process, from selecting his literary sources and camera lenses to the nature of the promotional campaigns and screening conditions in cinemas. His legendry stringency was a reflection of his desire to expect of his associates the same level of commitment and concentration he gave to his work. His watchword was always “If you don’t love the subject, let it go. There are too many mediocre movies”.

The spirit of the indomitable artisan endured in Stanley Kubrik, a creator who was able to define his identity through a body of work that, despite its scale, was always hand-made. In the words of the philosopher Eugenio Trias: “Just like the omnipotent God of the Judeo-Christian tradition, (Kubrick) was everywhere, he reached the most hidden corners, saw everything, supervised and governed it in an all-encompassing exercise in omniscience and with a panoptic vision hitherto unseen in the film-making adventure.” It wouldn’t be too far fetched to consider each of his film sas the sublimation of a desire to achieve complete control of the universe. Or, at least, of an imaginary universe that was always a scale reductionof ours.

Underpinned by a stylistic consistency whose distinguishing features can be found in the meticulous construction of the shot and the almost orchestral fluidity of the camera movements, Stanley Kubrick’s creative work also proposes a comprehensive gaze at the human, from its origins to its potential significance, covering a wide range of subjects, tones and atmospheres beneath which we can always spot the tension between fragile human emotions and ruthless institutional rationality.

“I think if I had gone to college I would never have become a director” sais Kubrick remembering his late-teenage years working as a press photographer on the prestigious magazine Look. A self-taught artist who inherited his father’s passion for chess and photography – he was given a professional Graflex camera for his thirteen birthday -, the young Kubrick, who was born in the Bronx, was unwilling to subject himself to the codes of conventional education. He founf in the streets of New York a special place of initiation from where he could observe the human through a lens that allowed him to place his sophisticated solutions for compositions at the service of subtle observations on everyday life in a city brimming with vitality at every corner.

Stanley Kubrik was one of those filmmakers as renowed for the films he made as the one he didn’t. A numebr of ideas piqued his curiosity between one project and another, potential films that , in many cases never went beyond the scriptwriting stage, or the mere attempt, and invite us to imagine another possible body of work, a ghost career in which several approaches to the Second War, Viking adventures, pornographic satires and even adaptations of famous novels like J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings and Umberto Eco’s Focault’s Pendulum, can coexist.

The exhibition at CCCB reviews the creative career of Stanley Kubrick from his formative years as a photographer at Look magazine, to his 12 feature films, closing with his projects that remained uncompleted or were taken on by other filmmakers. The show is a chronological look at the work of a genius of the cinema, the creator of masterworks in a wide variety of cinematographic genres. This in-depth exploration of the complete works of Kubrick presents more than 600 items, including moving images (some 40 audiovisuals); objects and material from the director’s personal archives (research and production documents, screenplays, stills, tools, costumes, models, cameras and lenses), and his correspondence with the talent that surrounded him. The director’s entire career is documented, beginning with his early short doumentaries and ending with his last film, Eyes Wide Shut (1999). All of Kubrick’s films are introduced, including masterpieces such as 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), A Clockwork Orange (1971), Barry Lyndon (1975) and The Shining (1980).

Kubrick fans will find key elements, props and original costumes in Kubrick’s films such as the star child and the man-ape costume from 2001: A Space Odyssey, the dresses of the twin sisters and Jack Torrance’s axe from The Shining, the “Born to Kill” helmet from Full Metal Jacket (1986) and the masks from Eyes Wide Shut and various pieces of film equipment with which Kubrick worked: hand and studio cameras, a Moviola editing table and a selection of camera lenses, including the ultra-fast Zeiss lens with which the candle-lit scenes in Barry Lyndon were filmed.

Info:

Stanley Kubrick

October 24 2018 – March 31 2019

CCCB

Centre de Cultura Contemporania de Barcelona

Curated by Hans-Peter Reichmann and Tim Heptner

© Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.

© Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.

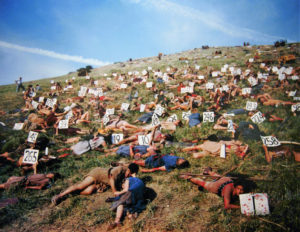

Spartacus scene photography, sequence of battle, reproduction, courtesy Deutsche Filmmuseum, Frankfurt

Spartacus scene photography, sequence of battle, reproduction, courtesy Deutsche Filmmuseum, Frankfurt

Peter Sellers as Dr. Strangelove in the War Room Film Still © Sony/Columbia Pictures Industries Inc.

Peter Sellers as Dr. Strangelove in the War Room Film Still © Sony/Columbia Pictures Industries Inc.

2001: A Space Odyssey, directed by Stanley Kubrick (1965-68; GB/United States) Film still © Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.

2001: A Space Odyssey, directed by Stanley Kubrick (1965-68; GB/United States) Film still © Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.

Lady Lyndon (Marisa Berenson) plays the piano with her son, Bryan Patrick Lyndon (David Morley), with tutor Reverend Samuel Runt (Murray Melvin), in the background Film Still © Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.

Lady Lyndon (Marisa Berenson) plays the piano with her son, Bryan Patrick Lyndon (David Morley), with tutor Reverend Samuel Runt (Murray Melvin), in the background Film Still © Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.

The Shining, Stanley Kubrick (1980; GB/United States), © Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.

The Shining, Stanley Kubrick (1980; GB/United States), © Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.

Actor and performer, he loves visual arts in all their manifestations.

NO COMMENT