It is always difficult to reconstruct the intellectual profile of an artist. Especially when it comes to someone like Marinella Pirelli (Verona, 1925-2009), one of the most secluded painters and filmmakers – and for too long considered outdated – of the Italian post-war period, recently rediscovered thanks to the retrospective that Museo del Novecento is dedicating to her in Milan, curated by Lucia Aspesi and Iolanda Ratti.

One of the reasons why Pirelli has long remained so peripheral is that she has never tried to adhere to properly definable schools and currents, nor she has ever been a victim of the artistic fashions of the moment; on the contrary, she has sometimes radically distanced herself, as after the death of her husband in 1973, when she decided to retire from the art scene and remain in the shadows for about twenty years, painting and growing peaches in a Veronese orchard.

Now, almost fifty years after that period of silence, even the visitor of the exhibition moves wrapped in shadow, going through a dozen rooms where the main light sources come directly from the works. The feeling is that of having come out of the buzz of our time and being immersed in a primitive space.

It does not seem a coincidence therefore that some works borrow their title from the world of astronomy: the Pulsars, for example, are optical devices that project intermittent and colored images on the wall, but carry the same name as the celestial bodies that, at the end of their own life cycle, emit sequences of radio wave impulses.

The same can be said of the series of sculptures called Meteores, aluminum frames that enclose colored and semi-transparent panels. On them a light and mobile source placed in front of them creates a play of lights with geometric shapes, causing the illusion of a lit monitor. In this way, Meteores not only questions the presumed fixity of analog images, but also expresses the artist’s desire to seek new ways of relating to the work, to push the visitor to come into contact with installations outside of the classic concept of art exhibition.

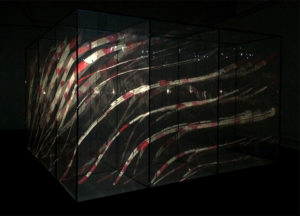

All of this is specified in Film Environment, a three-dimensional device that can be visited by spectators on which moving pictorial images are projected, with the result that those who cross it are flooded with beams of lights and colors.

At the same time time, Lucio Fontana and other Italian artists were already moving in the same direction and the idea of environment was certainly not unknown; what turns out to be farsighted here is the interaction generated by images coming from an electronic medium, the projector, with the human body, substantially new in that period and so widespread today.

Continuing in the exhibition itinerary, we arrive at later works, those in which a greater adjacency with the theoretical trends of the time stands out. In fact, the encounter with the feminist art critic and theorist Carla Lonzi dates back to the mid-1960s and, at the same time, the shift from the search for an image based on the visual rhythm and on the theory of colors to an investigation into one’s own being, where the presence of the body becomes more and more concrete.

This is the period of short 16mm films like Narciso, in which Pirelli takes up details of her body in a sort of intimate diary that analyzes them, looking for her identity as a woman, mother and artist, and Garments, a documentary film that records Luciano Fabro making a cast in tissue paper from Carla Lonzi’s breast.

The last film dates back to ’74, the year after the death of her husband Giovanni Pirelli, heir to the well-known tire industry. The film is called Double Self-Portrait and is introduced by a text by the artist which says: “In this film I filmed myself. I act simultaneously as an operator and as an actress. In the movement sequences I move with the camera in my hand facing me. No one controlled the image through the camera during the shoot. The camera was my partner: each of you is now my partner.”

In other words, none of us is ever really present in the self-view. For Marinella Pirelli there is always a limit, which is given by the impossibility of describing exhaustively the agent of the description. The ego cannot tell itself because it always remains an insoluble blind spot, an empty space in which to silently contemplate its absence.

Anna Elena Paraboschi

Info:

Luce Movimento. Il cinema sperimentale di Marinella Pirelli

a cura di Lucia Aspesi e Iolanda Ratti

22 marzo – 25 agosto 2019

Museo del Novecento

Piazza Duomo 8 Milano

Marinella Pirelli, Film Ambiente, 1969, struttura in acciaio, teli serigrafati, proiezioni luminose

Marinella Pirelli, Film Ambiente, 1969, struttura in acciaio, teli serigrafati, proiezioni luminose

Marinella Pirelli, Film Ambiente, 1969, struttura in acciaio, teli serigrafati, proiezioni luminose

Marinella Pirelli, Film Ambiente, 1969, struttura in acciaio, teli serigrafati, proiezioni luminose

Marinella Pirelli, Indumenti, 1966-67, pellicola 16mm

Marinella Pirelli, Indumenti, 1966-67, pellicola 16mm

Marinella Pirelli, primi anni ’50

Marinella Pirelli, primi anni ’50

Graduated in Visual Arts at the IUAV University of Venice, she attended design and photography classes at the Beaux Arts in Paris. She currently lives in Milan, where she studies painting and she is enrolled in the Master of Management of Exhibition Events at 24Ore Business School in collaboration with Pinacoteca di Brera.

NO COMMENT